Recovery packages cannot undermine fuel efficiency progress

The battle to move towards a cleaner, more efficient global fleet has been hard-fought, but as governments seek to jumpstart economies after COVID-19, they must resist pressure from vehicle manufactures to weaken legislation.

The auto industry was already facing a five-year global sales plateau, a decade of weak finances, and poor consumer confidence. The challenges of emerging technologies such as electrification, shared mobility, and automation were also biting, when the COVID pandemic came along. The combination of lockdowns closing many factories to safeguard workers’ health, limitations on movement dramatically reducing vehicle use, and widespread economic uncertainty saw sales stall.

Governments around the world are putting together stimulus packages in a desperate bid to kickstart their beleaguered economies. It is already clear that in some cases they are receiving industry appeals to roll back efficiency regulations under the auspices of lowering production costs. This false economy must be resisted. In reality, relaxing regulation would ultimately increase costs to drivers, weaken incentives for the transition to cleaner and more efficient vehicles, damage economies, and delay vital action to tackle climate change.

Improving vehicle efficiency means long-term financial savings. Modelling for the US’s original light-duty vehicle efficiency standards predicted $2,200 in benefits for 2025-30, set against an average increase in cost of just $600 per vehicle. The gains made in policy progress are, however, hard-won and easily lost; despite these promising cost-savings, the US administration has now revised its vehicle standards downward, a ‘fundamentally flawed’ decision, according to the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), which projected consumer buying a vehicle in 2025 would have recouped their investment within the third year of ownership.

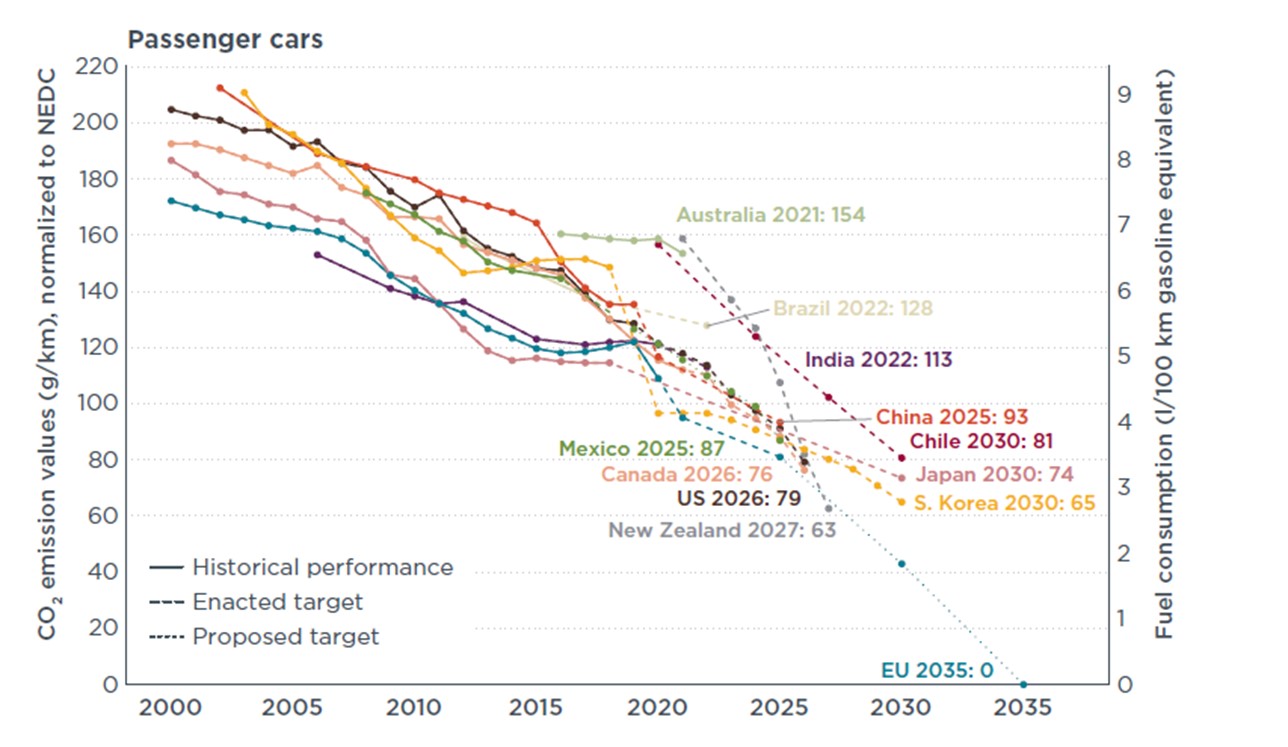

The impact of these measures, or their absence, has an impact beyond national borders; transport is responsible for around a quarter of global carbon dioxide emissions. Fuel efficiency measures have enormous potential for energy and emissions savings. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that fuel economy policies for passenger transport have saved 2.5 EJ of energy - equivalent to 348 million barrels of oil - between 2015 and 2018.

The Global Fuel Economy Initiative’s (GFEI) scenario modelling shows continuing improvement to road transport efficiency can significantly reduce carbon emissions. These efficiencies equate to a saving of five megatonnes of CO2 emissions, compared with currently adopted policies, with further improvements internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles improvements by 2050, even with further growth of the global fleet.

ICE improvements alone, however, are not enough. Even with improved engine efficiency, total emissions would be five times higher than the limits to achieve the Paris Agreement, which aims to curb global warming to within 1.5°C. Just as the COVID-19 pandemic has varying impacts on the health of individual counties but vast repercussions globally, so too the physical impact of climate change may be more obvious in certain regions but the global economic impact will be significant. The World Bank estimates some $390 billion a year is lost by households and firms due to disruption from climate challenges.

Electric vehicles (EVs) are an essential component of a cleaner, fuel-efficient fleet, however, while there has been some growth in more efficient electric powertrains, these still only make up a small proportion of sales. Governments need to accelerate the transition to EVs by recognising their greater efficiency compare to ICE, but also the increasing climate savings as the carbon intensity of the electricity grid improves over time. Fuel economy policy is increasingly being used to accelerate the transition to EVs, including through zero-emission vehicle mandates, which have been introduced in California and China. Actions taken within the next decade will be key for this transition; although batteries and charging infrastructure are rapidly improving, additional incentives are still needed in order to reduce emissions. Future investment in vehicle manufacturing needs to be focused on the transition to EVs to ensure cleaner mobility. Despite auto industry lobbying, this offers many opportunities for development and growth in new tech, in fact, a shift to low-carbon, resilient economies could create over 65 million net new jobs globally out to 2030 suggests the World Bank.

As governments consider economic stimulus and recovery, they must look to improve the fuel efficiency of their national fleet and play their part in an increasingly globalised economic and environmental policies. Now is the time to accelerate policies and investments to transform mobility with a focus on efficient, zero-emission, and low-carbon vehicles to achieve the changes to the global fleet to achieve the Paris Agreement target to future-proof jobs, citizens’ wellbeing and the planet.