The Chinese Automotive Fuel Economy Policy

"latest update provided by the Innovation Center for Energy and Transportation (iCET) China"

1.0 Background

China has been experiencing unprecedented annual sales growth rates since the beginning of the century. In 2014, vehicle sales in China suppressed 23 million units, marking the country's 6th straight year as the world's largest auto market. Although year-on-year growth has slowed since the economic crisis, annual sales in the past two years surpassed analysts’ predictions. China’s 2nd and 3rd tier markets are rapidly expanding leading to continuous high annual sales growth predictions, maintaining China’s predominant role as world’s largest car market in years to come. Even conservative estimates point to 2020 sales rate of 50 million units per year, which is comparable to total global vehicle sales in 2009, and to a total vehicle market of 550 million by 2050 (CAERC, 2013).

Not surprisingly, China has become the largest emitter of greenhouse gases and largest vehicle market in terms of annual growth, overtaking the U.S. China's transportation CO2 emissions have doubled from 2000 to 2010 and are projected to increase by a further 50% by 2020. Vehicle emissions are claimed to be responsible for about 31% of city PM2.5 in Beijing, and account for over 40% of city-center air pollution.

China has taken action to reduce its road transport greenhouse gas footprint by setting fuel economy regulations, putting in place a tax structure that seeks to give consumers an incentive to purchase more fuel efficient vehicles and limits the use of high-consuming vehicles (since 2006). Since 2005, the country’s rapidly growing new passenger vehicle market has been subject to fuel economy standards, and since 2010 new-energy vehicle adoption is receiving fiscal support. China has also committed itself to the scrapping of all yellow label vehicles, namely vehicles that fail to meet the Euro I emission standard, by 2017. Gasoline vehicle emissions, which have been subject to standards limits, have been increasing in stringency ever since and required to meet Euro V / Guo V standard nationally as of 2018 and be subjected to the official vehicle environmental certification.

China has more small cars overall than most other developed or developing countries, but larger cars are taking a larger share of the market. In 2012, vehicles below 1600cc captured over 40% of the private vehicle market and grew by over 6% annually, while 1600-2000cc captured 14% of the market, however grew by 8.37% (over the national average). In 2014 SUVs and Minivans achieved the largest market growth among vehicle segments. China’s driving patterns and average annual distance traveled have received limited research focus to date. However it can be assumed that the average distance traveled by private vehicle owners in China is about 20k km per year, lower than the US average, and decreasing to a projected 13k km by 2050. China’s poor fuel quality, on the other hand, may offset the emissions savings resulted from shorter vehicle distance travel.

1.1 The Chinese Light-Duty Vehicle Fleet

Since the turn of the century, China has experienced growth of over 1000% in vehicle stock, with tremendous increase projected to continue throughout coming decades. A study by China Automotive Energy Research Center (CAERC, 2013) predicts that the number of on-road vehicles in China will reach 550 million by 2050.

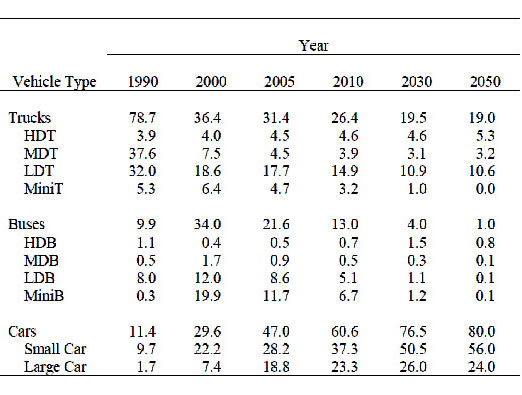

Sales data for calendar year 2014 indicates China’s light vehicle sales are about 19.7 million. This figure includes sales of 7.3 million vans, MPVs and SUVs, while MPVs and SUVs sales increased by 40%. The figure below shows a projection of China’s market share of light duty vehicles.

Projected Market Share of Each Vehicle Type (%), China

1.2 Status of LDV fleet fuel consumption/CO2 emissions

China’s fuel consumption and emissions are determined by the “New European Driving Cycle”, or NEDC, which is a stylized cycle consisting of 4 repeats of a city cycle with an average speed of 18.7 km/h and a highway cycle of with an average speed of 62.6 km/h and a maximum speed of 120 km/h. There are currently about 27 test grounds in China under the national Vehicle Emission Control Center (VECC) supervision subordinated to the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP), operationally approved by China National Accreditation Service for Conformity Assessment (CNAS) and providing fuel consumption data certified by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT).

China introduced fuel economy standards for light duty passenger vehicles in September 2004 targeting a fuel consumption of 6.9L/100km by 2015, which translates to an estimated 167g/km of CO2 emissions. The standard was initially outlined in two phases - the first phase rolled out from July 2005 and the second phase from January 2008 (were existing vehicle production started implementation a year after new-vehicle production). Phase 1 (2005) of the fuel economy standard increased the overall passenger vehicle fuel efficiency by approximately 9%, from 12L/100km in 2002 to 11L/100km in 2006, despite increases in gross weight and engine displacement. It is estimated this saved approximately 575,000 tons of oil and 1.7 million tones of CO2 emissions between 2002 and 2006. This has also made Chinese fuel economy standard the 3rd most stringent in the world, behind the EU and Japan.

In 2009, the national average fuel consumption stood at 7.78L/100km equivalent to 180.5 CO2g/km, but by 2010 it had risen by 0.6% to 7.83 L/100km, or an equivalent of 181.7CO2 g/km. From the distribution of car models sold in 2009 and 2010, it is evident that the proportion of new cars sold with fuel efficiencies below 8.0 L/100km stood at roughly 70%, but by 2010 this proportion had dropped down to roughly 60%. The change is closely linked to the fact larger engine displacement and high fuel consuming cars are increasing their market share.

In 2011, a third phase to the fuel economy standard has been introduced, targeting fuel consumption of 5L/100km by 2020, which translates to an estimated of 120g/km CO2 emissions and adding corporate average fuel consumption target to the original vehicle-based standard. By 2011, the implementation of the first two phases showed successful reduction of some 11.5% in average fuel consumption and resulted emissions. However, there is some concern that the increasing size and mix of China’s vehicle fleet may overwhelm these initial gains. Furthermore, as auto manufacturers are steadily meeting their corporate annual goals, raising concerns over the level of stringency and effectiveness of existing standards (iCET, 2012).

2.0 Regulatory Policies

2.1 National Standard

China has put a set of fuel economy standards in place. The first two phases of the standards (2004-2012) was unique in the world because there was no corporate averaging allowed in meeting the weight-bin based vehicle limit standard. Every individual car is evaluated against the weight-based standard limit, and the official fuel consumption (FC) figure is determined at the type-approval. There is, however, a separate requirement for corporate average fuel consumption on top of the model-based requirement since the standards’ third phase implemented as of 2012 (namely, the CAFC target), which allows for corporations to average their fleet FC within a specified boundary from the target year (2015 and then 2020) and according to a per-vehicle weight-bin target.

Serial Number |

Standard Title |

Issuance |

Implementation |

Comments |

GB/T |

Vehicle Classification |

Replaced GB/T 15089-1994 |

||

GB/T 19233-2003 |

Measurement methods of fuel consumption for light duty vehicles |

16/2/2006 |

1/4/2006 |

|

GB19578-2004 |

Fuel consumption limits for passenger cars |

2/9/2004 |

New vehicles: Phase I from 1/7/2005 |

First of its kind; Governing gasoline and diesel fueled vehicles with minimum speed of 50km/h and maximum weight of 3500kg |

GB20997-2007 |

Fuel consumption limits for light commercial duty vehicles |

1/2/2008 |

1/1/2011 |

First of its kind; Governing gasoline and diesel fueled vehicles with curb weight equal to or above 2000kg which are meant for commercial use |

GB19233-2008 |

Measurement methods of fuel consumption for light duty vehicles |

3/2/2008 |

1/8/2008 |

Replaced GB19233-2003; Details for the implementation of GB19578-2004; Governing gasoline and diesel powered M1, M2, N1 vehicles not exceeding 3500kg |

GB27999-2011 |

Fuel consumption evaluation method and targets for passenger cars |

30/12/2011 |

1/1/2012 |

Details for the implementation of GB19578-2004; Governing gasoline and diesel powered passenger vehicles not exceeding 3500kg |

GB19578-2014 |

Fuel consumption limits for passenger cars |

22/12/2014 |

1/1/2016 |

Draft for replacing GB19578-2011; Governing gasoline and diesel powered passenger vehicles not exceeding 3500kg |

GB 27999—2014 |

Fuel consumption evaluation methods and targets for passenger cars |

22/12/2014 |

1/1/2016 |

Draft for replacing GB 27999—2011; |

Notes: There are three types standards related to Fuel Economy in China: (1) Testing standards - National standards/”GuoBiao” No.19233, currently two such standards were announced (the 2008 standards replaced the 2003 standard); (2) Fuel consumption limit - National standards/”GuoBiao” No. 19578, currently one such standards (the December 2014 declared standard is meant to replace the 2004 standards); (3) Fuel consumption target standards - National standards/”GuoBiao” No.27999, currently one such standards (the December 2014 declared standard is meant to replace the 2011 standards).

Source: compiled by iCET, 2015 update

The Chinese government issued its first vehicle fuel consumption related policy in 2004 with the national standard of "Limits of Fuel Consumption for Passenger Cars" (GB 19578-2004), targeting an average fuel consumption of 6.9L/100km by 2015 which translates to CO2 emissions of 167kg/km. The standard was meant to be implemented gradually and thus was instructed in two initial phases - the first for 2005 newly-produced vehicles (followed by full segment production compliance in 2006) and the second for 2008 newly-produced vehicles (with full segment production compliance in 2009).

The initially included segments were passenger cars, SUVs, and light commercial vehicles (LCVs), collectively defined M1-types vehicles by the EU, or as defined in the original Chinese standard –vehicles with minimum speed of 50 km/h and maximum weight of 3500 kg. The Chinese standards as well as its EU testing method are based on this vehicle segmentation; however, it is claimed that as the driving cycle in China differs from the EU driving cycle, the test may have little value in reflecting real-world driving fuel consumption and emissions. A recent report claimed real-world and test discrepancies can reach 30%. In 2007 a fuel consumption limits for light commercial duty vehicles was set, governing gasoline and diesel fueled vehicles with curb weight equal to or above 2000 kg meant for commercial use. Thereafter, fuel consumption standards for vehicles exclude this segment, which is governed by a separate standard regime.

The third phase of passenger vehicle standard includes corporate average fuel consumption (CAFC) target (GB 27999-2011), which went into effect in 2012 and meant to become binding as of 2015. The CAFC target (GB 27999-2011) and the passenger car fuel limits standard (GB 19578-2004) are designed to realize an ambitious average fuel consumption target of 6.9 L/100km by 2015 (translating to about CO2 163 kg/km). The fourth phase recently released is providing gradual implementation guidelines towards a 2020 5.0 L/100km binding target.

The corporate average fuel consumption target (TCAFC) was set for car automakers (and importers). In the below detailed explanation of the TCAFC calculation, CAFC/TCAFC will represent the indicator national standard (GB 27999) target implementation status. The CAFC uses vehicle model, year, and annual sales to calculate a weighted average for fuel consumption based on the New European Driving Cycle (NEDC), as shown in the formula below:

The CAFC Target is based on individual vehicle fuel consumption targets, which uses the quantity of annual sales of each model to calculate a weighted average. See the formula below:

The gradually changing fuel consumption targets are designed to account for the time that vehicle manufacturers need for product planning, technology upgrades, and developing new vehicle models. The CAFC requirement was enacted in 2012 and allows automotive manufacturers until 2015 to gradually reduce their fuel consumption levels and meet the target, towards the CAFC binding period starting in 2015.

Based on the requirements for individual vehicle limit standards as well as cooperate average fuel consumption standards, the national annual fuel target was steering weight-bin target values below the standard “limit” values, and determined by the corporate model mix and sales per model.

|

Year |

CAFC/TCAFC requirement allowance |

CAFC targetL/100km |

Annual FC reduction L/100km |

Phase III |

2012 |

109% |

7.5 |

N/A |

2013 |

106% |

7.3 |

0.2 |

|

2014 |

103% |

7.1 |

0.2 |

|

2015 |

100% |

6.9 |

0.20 |

|

Phase IV |

2016 |

134% |

6.7 |

0.20 |

2017 |

128% |

6.4 |

0.30 |

|

2018 |

120% |

6.0 |

0.40 |

|

2019 |

110% |

5.5 |

0.50 |

|

2020 |

100% |

5.0 |

0.50 |

Source: iCET, 2013

The March 2013 issued CAFC accounting method further details two flexibility schemes for the implementation of the annual corporate average fuel consumption limit value: first, passenger car models with a pure electric range of 50km or more can be counted five times, and models with combined fuel consumption lower than 2.8 L/100km can be counted three times. Meaning, a low fuel consuming vehicle can carry heavier weight and thus provide corporate fuel consumption score that is lower than what it would have been otherwise. This flexibility is intended to incentivize the production of new-energy vehicles, but also creates adverse effect by allowing for more fuel consuming vehicles to exist in a given corporate fleet. The second flexibility mechanism is the ability to transfer excess or surplus of CAFC from a given year to the following years (within three years).

Government ministries can therefore control the average fuel consumption level of each manufacturer and the national average fuel consumption level since the third phase of national standard, thereby strengthening energy conservation management of the automotive industry. The standard have developed in a way that brought the fuel economy system one step closer to completion by promoting low-energy consuming vehicles, reducing the average size and weight of Chinese–produced vehicles, and raising the Chinese automotive industry’s overall fuel economy level.

The phase IV fuel economy standards implementation framework in China was aligned with phase III. It is comprised of more ambitious individual car fuel limits (GB 19578-2014) and cooperate average fuel consumption (CAFC) target (GB 27999-2014). It was approved in December 2014 and expected to take effect from 2016 to 2020 targeting 5.0 L/100km.

The new standard individual car fuel consumption limits are stricter by about 20%, and vehicle types are no longer divided to manual and automated transition but rather according to a combination of curb weight and seat rows numbers. A further new addition of the standard is the inclusion of energy saving and new-energy vehicles (CNG, plug-in hybrids, pure electric vehicles, fuel cell) and advanced fuel efficiency improvement technologies (idle start-stop, shift reminder, tire pressure monitoring system, and efficient air conditioning). For every vehicle that incorporates fuels other than conventional gasoline and diesel, the standard point to an existing energy consumption directory of provided fuel consumption measurement instructions. For vehicles that have installed one of the stated fuel consumption technologies, a reduction of fuel consumption of up to 0.5L/100km is allowed.

The current fuel consumption standard is built on 16 weight classes and has two versions: one for manual transmissions vehicles and another for vehicles that are either with an automated transmission or with three rows of seats and above. Currently, for manual vehicles, which are losing market share in the passenger car segment (stood at 56% in 2012 after losing 8% in three years), the smallest weight class is defined as below 750 kg with 5.2L/100km requirement (for 2015), further 8 classes are below 1660kg with up to 8.1 L/100km, and additional 7 classes are placed above these weights with a maximum consumption of 11.5 L/100km. For automated and three seat-rows vehicles the classes are similar, yet fuel consumption requirements are generally less stringent (5.6L/100km for lowest class, 8.4 L/100km for 1660kg, and up to 11.9L/100km).

Phase IV is designed to increase cars’ fuel consumption limits by about 20% and fuel consumption targets by 30%-40%. The new standard provides more detailed technology pathways for reducing fuel consumption and further promotes new energy vehicles by detailing their relative fuel consumption calculation. The new standard requires an accelerated annual corporate average reduction rate of roughly 3% in the first year (2016) to about 9% in the last two years (2019 and 2020).

China weight-based passenger vehicle fuel consumption limits (Phases I, II and III) for automatic transmission (AT) and manual transmission (MT) vehicles: Graphic illustration

China weight-based passenger vehicle fuel consumption limits (Phases I, II and III) for automatic and manual transmission vehicles: Table illustration

Fuel Consumption Limits for Phase I, II, III Standard and Targets for Phase III, by Weight Class |

|||||||||||

Curb Mass (CM) (kg) |

Phase I Limits |

Phase II+III Limits |

Phase III Targets |

Phase IV Limits |

Phase IV |

||||||

As of July 2005 for new, July 2006 for all |

As of July 2008 for new, July 2009 for all |

As of January 2012 |

As of 2020 |

||||||||

MT |

AT and/or >= 3seat row |

MT |

AT and/or >= 3seat rows |

MT |

AT and/or >= 3seat row |

MT |

AT and/or >= 3seat row |

>=2 seat rows |

3 seat row and cw <= 1090kg |

3 seat rows and cw> 1090kg or > 3 seat rows |

|

CM≤750 |

7.2 |

7.6 |

6.2 |

6.6 |

5.2 |

5.6 |

5.2 |

5.6 |

3.9 |

4.1 |

4.0 |

750<CM≤865 |

7.2 |

7.6 |

6.5 |

6.9 |

5.5 |

5.9 |

5.5 |

5.9 |

4.1 |

4.3 |

4.2 |

865<CM≤980 |

7.7 |

8.2 |

7 |

7.4 |

5.8 |

6.2 |

5.8 |

6.2 |

4.3 |

4.5 |

4.4 |

980<CM≤1090 |

8.3 |

8.8 |

7.5 |

8 |

6.1 |

6.5 |

6.1 |

6.5 |

4.5 |

4.7 |

4.6 |

1090<CM≤1205 |

8.9 |

9.4 |

8.1 |

8.6 |

6.5 |

6.8 |

6.5 |

6.8 |

4.7 |

- |

4.8 |

1205<CM≤1320 |

9.5 |

10.1 |

8.6 |

9.1 |

6.9 |

7.2 |

6.9 |

7.2 |

4.9 |

- |

5.0 |

1320<CM≤1430 |

10.1 |

10.7 |

9.2 |

9.8 |

7.3 |

7.6 |

7.3 |

7.6 |

5.1 |

- |

5.3 |

1430<CM≤1540 |

10.7 |

11.5 |

9.7 |

10.3 |

7.7 |

8 |

7.7 |

8 |

5.3 |

- |

5.5 |

1540<CM≤1660 |

11.3 |

12 |

10.2 |

10.8 |

8.1 |

8.4 |

8.1 |

8.4 |

5.5 |

- |

5.7 |

1660<CM≤1770 |

11.9 |

12.6 |

10.7 |

11.3 |

8.5 |

8.8 |

8.5 |

8.8 |

5.7 |

- |

5.9 |

1770<CM≤1880 |

12.4 |

13.1 |

11.1 |

11.8 |

8.9 |

9.2 |

8.9 |

9.2 |

5.9 |

- |

6.1 |

1880<CM≤2000 |

12.8 |

13.6 |

11.5 |

12.2 |

9.3 |

9.6 |

9.3 |

9.6 |

6.2 |

- |

6.4 |

2000<CM≤2110 |

13.2 |

14 |

11.9 |

12.6 |

9.7 |

10.1 |

9.7 |

10.1 |

6.4 |

- |

6.6 |

2110<CM≤2280 |

13.7 |

14.5 |

12.3 |

13 |

10.1 |

10.6 |

10.1 |

10.6 |

6.6 |

- |

6.8 |

2280<CM≤2510 |

14.6 |

15.5 |

13.1 |

13.9 |

10.8 |

11.2 |

10.8 |

11.2 |

7 |

- |

7.2 |

CM>2510 |

15.5 |

16.4 |

13.9 |

14.7 |

11.5 |

11.9 |

11.5 |

11.9 |

7.3 |

- |

7.5 |

* Note: Phase IV also include hybrid cars, the method for calculating fuel consumption is based on

Source: iCET, 2014

China announced its first heavy-duty vehicle Phase I standards in 2011 (QC/T 924-2011), effective as of July 1 2012 for new vehicle type approvals. This standard was meant to inform the design of the second phase standards finalized in February 2014 (GB 30510-2014). Phase I of the standard was unique in that is was design on the basis of an over two years study that included lab tests of about 300 locally produced state-of-the-art existing fleet vehicles. Passenger fuel economy vehicle standards could also benefit from a stringency evaluation based on the status and technology roadmap of China’s unique vehicle fleet.

2.2 Import restrictions

New Vehicles

N/A

Second Hand

China bans the import of used vehicles for uses other than personal. Also diesel vehicles (except Jeeps) and two-stroke engine cars are prohibited from importation.

2.3 Technology mandates/targets

There are no technology mandates in China, but rather a set of regulations meant to encourage technology transfer to China (e.g. joint-venture requirements and industry consolidation efforts).

3.0 Fiscal Measures and Economic Instruments

3.1 Fuel Taxes

The National Development and Reform Commission raised gasoline excise tax from 0.2 Yuan to 1 Yuan per liter and diesel excise tax from 0.1 Yuan to 0.8 Yuan per liter as of Jan 1st 2009, following a 2008 year-end announcement.

In conjunction with global oil prices fluctuations, China’s fuel price continuously decreased in 2013 and 2014. The central government seized this opportunity to increase fuel excise tax several times. By January 12 2015, gasoline excise tax was 1.52 Yuan per liter.

3.2 Fee-bate

As part of the plan to cut fuel emissions in the world’s largest vehicle fleet, China spent about $1.76 billion to subsidize smaller, fuel-efficient cars by 2012. The Chinese National Development and Reform Commission are announcing on periodic basis eligibility of vehicles for receiving the subsidy. It is estimated that by 2012, 4 million energy-saving and new-energy vehicles will be eligible, according to the National Development and Reform Commission. The subsidies were extended until the end of 2015, however the 3,000 Yuan subsidy is offered to vehicles meeting the below requirements:

- Engine displacement smaller than 1.6 L

- Fuel consumption level as follows: (new condition)

Curb Mass (kg) |

2 seat rows (L/100 km) |

>=3 seat rows |

CM≤750 |

4.7 |

5.0 |

750<CM≤865 |

4.9 |

5.2 |

865<CM≤980 |

5.1 |

5.4 |

980<CM≤1090 |

5.3 |

5.6 |

1090<CM≤1205 |

5.6 |

5.9 |

CM>1205 |

- Tailpipe emissions meet the GUO V emission standards (new condition)

As of 2013, subsidies have been offered to buyers of New Energy Vehicle (NEVs) models in five cities. Citizens of Shanghai, Shenzhen, Hangzhou, Hefei and Changchun can receive up to 50,000 Yuan in subsidies if they buy plug-in hybrid cars. For those who purchase fully electric vehicles, the subsidy is 60,000 Yuan. The subsidies are not handed out to the consumer however, but forwarded to the automakers who then lowers the sticker price of the vehicles in car showrooms.

Although these subsidies alone are not sufficient to drive mass production and commercialization of green vehicles, it at least motivates “first-movers” to purchase an electric or hybrid vehicle. The government has stated to further direct and fund the construction of charging points and battery recovery networks in the pilot cities, which are recognized as major barriers to market uptake.

3.3 Buy-back

China has committed itself to the scrapping of all yellow label vehicles (vehicles that fail to meet the Euro I emission standard) by 2017. Detailed execution plan and methods have yet to be announced.

3.4 Penalties

China revised its taxation of motor vehicles in order to strengthen incentives for the sale and purchase of vehicles with smaller engines. The taxation has two components: an excise tax levied on automakers and a sales tax levied on consumers. The excise tax rates are based on engine displacement. In 2006, the Chinese government updated excise tax rates to further encourage the manufacture of smaller-engine vehicles. Specifically, the tax rate on small-engine (1.0-1.5 liter) vehicles was cut from 5 to 3 percent, while the tax rate on vehicles with larger-engines (more than 4 liters) was raised from 8 to 20 percent. Also, as the preferential 5 percent tax rate that applied to SUVs has been eliminated, all SUVs are now subject to the same tax schedule as other vehicles with the same engine displacement. The excise tax was adjusted in 2008 again, continuing to encourage small cars by decreasing <1.0 L engine vehicle excise tax to 1%, while discouraging large car by increasing excise tax of 3.0-4.0L and above 4.0L engine vehicles to 25% and 40% respectively.

Category by engine displacement (L) |

Tax rate prior to 4/1/2006 |

Tax rate 4/1/2006-8/31/2008 (%) |

Tax rate beginning 9/1/2008 (%) |

<1.0 |

3 |

3 |

1 |

1.0-1.5 |

5 |

3 |

3 |

1.5-2.0 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

2.0-2.5 |

5* |

9 |

9 |

2.5-3.0 |

8 |

12 |

12 |

3.0-4.0 |

8 |

15 |

25 |

4.0 and larger |

8 |

20 |

40 |

* Note: Between 1994-2006 engine size groups were slightly different than today, according to which the excise tax for <2.2L was 5% and for>2.2L it was 8%.

3.5 Other tax instruments

The Chinese government offers a nationwide subsidy of RMB 3,000 (about USD 450) to consumers who purchase any passenger vehicle (of any fuel type including hybrid) which have an engine capacity of under 1.6-litre and that consume 20% or less fuel than government standards.

3.6 Registration fees

The Vehicle Acquisition Tax (single registration fee) shall be calculated using the ad valorum rate, in accordance with the following formula: Vehicle Acquisition tax payable = Taxable value X Tax rate. The vehicle acquisition tax basic rate is 10%.

However, a preferential rate exists for defending the auto industry from crisis, such as the global financial crisis of 2008: the government implemented the “Automobile Industry Restructuring and Revitalization Plan” in early 2009, stating that acquisition tax for vehicles with displacement <1.6L would be 5% between January and December 2009 and 7.5% between January and December 2010.

Beyond the actual fee paid at vehicle registration, a license plate fee is also charged in most Chinese cities. The license fee has typically resulted from limited license plate quotas defined by local governments in an attempt to curve local congestion and vehicle emissions, which can be won through bids or lottery schemes. The more demand there is for every single license plate, the more expensive the license plate is. In some cities, the price ceiling has been set in an attempt to curb costs, which has RMB100,000 in some cases (caps and fees are further discussed in section 4.3).

3.7 R&D

The government has created some incentives to spur R&D for accelerating the shift towards low-carbon transportation. In support of indigenous innovation and development of the auto industry, the government announced a dedicated budget of USD 1.46 billion specifically for automotive technology innovation and the R&D of new energy automobiles and components. Attractive technology improvements for key automotive components include electric motors, batteries, electric controls, engines, gearboxes, brake systems, steering systems, transmissions, suspension systems and automobile control systems.

The central government plans to allocate over USD 15 billion to support the development of energy efficient and new energy vehicles between 2011 and 2020. The details, which are awaiting approval by the Ministry of Finance, are: USD 7.5 billion from 2011 to 2020 for the R&D and industrialization of energy efficient and new energy cars; USD 4.5 billion from 2011 to 2015 for the deployment of new energy car pilot projects; USD 3 billion from 2011 to 2015 for the promotion of hybrid electric vehicles and other energy saving cars; USD 1.5 billion from 2011 to 2015 for the development of key components; and USD 750 million from 2011 to 2015 for the deployment of electric vehicle infrastructures in the pilot cities (as of 2013 there are 28 NEV pilot cities city clusters in China, projected to be evaluated in 2015).

4.0 Traffic Control Measures

4.1 Priority lanes

Currently, driving restrictions in most cities are imposed on China I emissions standard for gasoline vehicles and China III emissions standards for diesel vehicles (the Chinese standards are similar to the EU emissions standards).

The most advanced vehicle usage restrictions are in Beijing. Beijing imposed restrictions on vehicles registered outside of its jurisdiction area and also on vehicle purchase within its jurisdiction. On October 1, 2009 China's environment authorities banned motor vehicles registered outside of Beijing from entering the capital city if they fail to meet exhaust emissions standards. The Ministry of Environmental Protection mandated that petrol vehicles are not allowed to travel along or within Beijing's Sixth Ring Road, the city's outermost highway loop, if their exhaust emissions do not comply with National Emission Standard I. Diesel-driven vehicles must comply with National Emission Standard III or above before they can operate in the same area. The rule applies to vehicles registered outside Beijing because many regions have not yet made the standards mandatory.

4.2 Parking

N/A

4.3 Road pricing

Chinese cities are using measures, like charging congestion fees or parking fees, to control the rising demand for car ownership in order to prevent congestion and curb pollution. One of Chinas’ unique traffic control measurements is in the license plate caps, imposed on the municipal level. Beijing, Shanghai, Guiyang, Guangzhou, Tianjin and other cities have already enacted methods such as license plate lottery (with or without price ceiling) and/or auction since 2011. Furthermore, separate license plates quotas have been put in place in several cities already, increasing NEV adoption.

For instance, Beijing introduced its license plate cap and lottery in 2011, decreasing vehicle sales from 20,000 a month between 2005 and 2010 to an average monthly of 14,600 and 18,000 in 2011 and 2012, respectively. Beijing is aiming at limiting the total number of vehicles registered to 6 million by the end of 2017, which means more stringent limitation will apply between 2014 and 2017 with vehicle sales of less than 12,000 a month. This translates to about only 1 for every 84 people participating in the bid will receive a vehicle license plate, based on annual application average to date. In early 2014 Beijing have issues new license plate quota for NEVs of some 20,000, encouraging NEVs adoption.

5.0 Information

5.1 Labeling

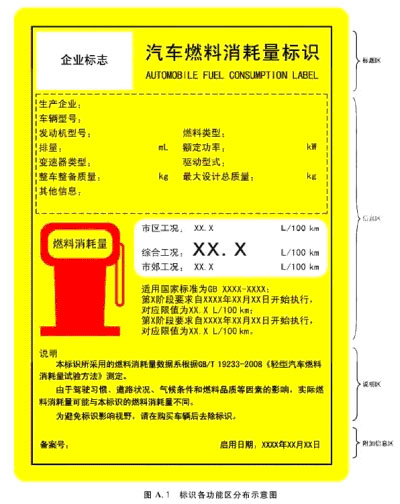

In order to strengthen the automotive industry's energy management and related sales impacts, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) has formally implemented China's first "light vehicle fuel consumption labeling regulations" as of July. The label is as follows:

The white box top left (where it says 企业标志) is the place for the car manufacturer's logo. The white box center right contains 3 economy listings in litres per 100 km. The first is for urban conditions -- 市 区 工 况 , the second good driving conditions -- 续合工况 , and the third for congested city conditions - 市 耜 工 况

The label’s uptake is however low. Two years after the "Light vehicle fuel consumption labeling regulations" was implemented with the aim of strengthening energy conservation management of vehicles, iCET has taken on the task of assessing market compliance with this new rating system by researching a sample of China's municipal 4S auto shops' models labeling (0.54% sample size). Among 16 cities researched, a total of 864 vehicles presented at 114 4S shop car showrooms have had a fuel consumption label, representing some 62% market uptake. Imported cars accounted for only 26% of the labeled cars, while joint venture brands vehicle labeling was 67% and own-brands labeling was 62%. This study unveils that there is a lot of room for both educating the general public regarding fuel consumption impacts on vehicle's practical usage as well as improving the method and visualization of labeling for enhancing the new regulations' implementation and impacts (iCET, 2012).

China Automotive Technology & Research Center (CATRAC) initiated work aimed at suggesting a new label draft design in July 2012. Although the work was estimated to end with a draft design in August 2013, no new label draft has been announced yet.

5.2 Public info

Vehicle’s sales and fuel consumption are publically released around the middle of the second annual quarter, by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT). Vehicle and corporate fuel economy information is also available on China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM) website (however typically with some data discrepancies).

Official vehicle fuel consumption and corporate average fuel consumption data is originated at corporate mandatory submissions part of the CAFÉ regulatory scheme. The fuel consumption level of each vehicle is determined at the Type Test Approval supervised by the Vehicle Emissions Control Center (VECC), under the Ministry of Environmental Protection, and authorized by under China National Accreditation Service for Conformity Assessment (CNAS) under CNCA. The corporate average fuel consumption values, which are provided by the companies, are based on each vehicle’s type approval certificate and the corporate reported sales numbers.

Various voluntary schemes offering green ratings of vehicles have evolved in recent years, in an attempt to highlight overall lifecycle emissions based not only on use-stage fuel consumption but rather on a more comprehensive life-cycle assessment. Furthermore, as official fuel consumption figures are based on figures provided by the companies, and the type approval figures are EU-cycle lab illustration of prototype vehicles provided by each manufacturer, the credibility of these official fuel economy figures is questionable. An April 2014 report states discrepancies between MIIT reported data and real life fuel consumption reach 30%. As of its annual 2013 report and 2014 online system adjustment, iCET’s EFV is offering is basing its vehicle rating based on selected real-world vehicle emissions data provided by China Vehicle Control Emissions Center of the Ministry of Environmental Protection (VECC-MEP).

5.3 Industry reporting

In order to improve vehicle management and in accordance with the 2012 announced "State Council’s energy-saving and new energy automotive industry development plan (2012-2020)", a joint-ministerial effort comprised of the Ministry of industry and Information Technology (MIIT), the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM), and Customs General Administration (AQSIQ) jointly developed an "Accounting Approach for Passenger Vehicle Corporate Average Fuel Consumption". The accounting approach was announced in March 2013 and entered into effect on May 1st 2013.

China’s new accounting approach sets forth the following binding industry reporting requirements: Vehicle manufacturers are obliged to report to the Ministry of Industry and Information technology (MIIT) on their expected calendar year corporate annual average fuel consumption by December 20 of each year. By August 1st of each calendar year, the first year-half actual average corporate fuel consumption results should be reported. By February 1st of each calendar year, the actual corporate average fuel consumption of the previous year should be reported. The approach does not specify penalties in case of lack of, inadequate, or false reporting, and does not provide specific enforcement measurements. Corporations that fail to or provide inadequate reporting are subject to legal procedures as stated by the court of law. Enforcement authority is not specified.

On May 5th 2014 the MIIT published for the first time a list of auto manufacturers’ average corporate fuel consumption scores for the year 2013. The list introduced average fuel consumption data provided directly by the submitting companies (totaling 104), as well as a list of 7 manufacturers that failed to submit their corporate average fuel consumption data as required. The announcement was aimed at increasing transparency towards this year’s 106% average requirement from 2015 targeted 6.9L/100km. The announcement also served as an official call for comments (due by June 7th 2014).

On May 15 2014, the MIIT further announced that a working group led by its industry division and equipment department would inspect approval testing to ensure sound implementation of China’s third phase fuel consumption aimed at an average of 6.9L/100km by 2015. For the first time, the Ministry had officially announced that penalties would occur, however no specification of prices or process have been announced.

The text above is a summary and synthesis of the following sources:

- An, Feng, et al. "Passenger Vehicle Greenhouse Gas and Fuel Economy Standards: A Global Update." The International Council on Clean Transport (2007): 1-36.

- An, Feng and Sauer, Amanda. "Comparison of Vehicle Fuel Economy Standards and Greenhouse Gas Standards Around the World." Pew Center on Global Climate Change, 2004: 14.

- China Automotive Energy Research Center (CAERC), “Technologies and Policies for Sustainable Automotive Energy Transformation in China.”2013

- Fulton, L. "International Comparison of Light-duty Vehicle Fuel Economy and Related Characteristics." International Energy Agency Working Paper Series, 2010: 1-70.

- Innovation Center for Energy and Transportation (iCET), “China Passenger Vehicle Corporate Average Fuel Consumption (CAFC) Trend Report”, 2011

- Innovation Center for Energy and Transportation (iCET), “China Fuel Consumption Labeling Implementation Study”, 2012

- Innovation Center for Energy and Transportation (iCET), “2012 China Environmentally Friendly Vehicle Report”, 2013

- Innovation Center for Energy and Transportation (iCET), “2012 China Passenger Vehicle Corporate Average Fuel Consumption Report ”, 2013

- Innovation Center for Energy and Transportation (iCET), “Performance of the Chinese New Vehicle Fleet Compared to Global Fuel Economy and Fuel Consumption Standards.” The Energy Foundation, 2014

- Walsh, M. Car Lines. Issue 2010 (3), June 2010 : 45.

- Oliver et al. (2009). "China’s Fuel Economy Standards for Passenger Vehicles: Rationale, Policy Process, and Impacts" Discussion Paper, Cambridge, Mass.: Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, 2009: 4.

- Oliver, H. "Assessing the Impacts of Chinese Fuel Economy Standards for Light-duty Passenger Vehicles." 11 October 2007. Accessed 7 October 2009.

- "Passenger Vehicles, GHG and Fuel Economy Standards." International Council on Clean Transport, 2007

- Zhao, J. and Meliana, M. "Transition to hydrogen-based transportation in China: Lessons learned from alternative fuel vehicle programs in the United States and China." Elsevier, 2006: 1604.

- Wang, M. et al. "Projection of Chinese Motor Vehicle Growth , Oil Demand, and CO2 Emissions Through 2050." The Energy Foundation, 2006