Developing Chile's Automotive Fuel Economy Policy

1.1 Background

Chile ratified the Kyoto Protocol in 2002 and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1995. While Chile currently has no binding international or national obligations to reduce GHG emissions, the country is an active member in UN-led global climate change negotiations and embraces the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities for a post-Kyoto framework.

Unlike many of its South American neighbors, Chile has limited indigenous fossil energy resources. Yet, fossil fuels account for almost 80% of the country’s total primary energy supply. As a result, Chile imports close to 75% of its primary energy in the form of oil, gas and coal.

1.2 Chile’s Light-Duty Vehicle Fleet

Chile’s transport sector relies almost entirely on petroleum-based fuels. Gasoline dominates, although diesel has been increasing in recent years, likely in part due to diesel’s more favorable treatment under fuel excise tax policy. Alternative fuels, including bio-fuel mixes for transport, receive a slight fuel tax advantage. Any major shift from petroleum as the primary energy source for the transport sector in the medium term seems unlikely.

Spurred in large part by the need to address Santiago’s air pollution problems, the country has embarked on aggressive transportation fuel quality improvements in recent years. Unleaded gasoline was first introduced to Santiago in 1991 (to accommodate the influx of cars with catalytic converters), and since April 2001 the sale of leaded gasoline has been discontinued, nation-wide. For diesel, nationwide the maximum sulphur content is already 50 parts per million (ppm), while in Santiago the diesel sulphur norm will be lowered to 15 ppm in September 2011.

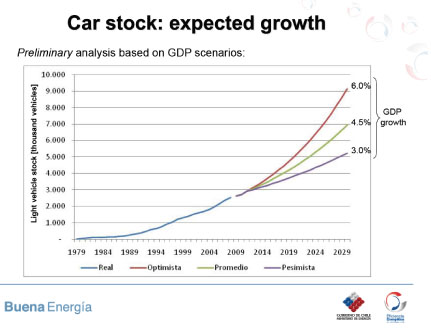

The Chilean domestic vehicle fleet has shown an average growth rate of 13% between 2005 and 2010, except for 2008, where there was a stagnation as a consequence of the international financial crisis where sales decreased by 8%. The segment of larger vehicles, such as light duty trucks and SUV’s, has increased significantly, growing 242% in the 2005-2010 period, accounting for almost a third of automobile sales, which affects a larger size and average displacement market. The national legal framework also has an effect on this phenomenon, distortions such as tax rebate for the purchase of light duty trucks and four wheel drive vehicles.

In Chile, the vehicles approved under EURO emission standards have displaced those certified under EPA standards. Diesel technology vehicles have progressively gained a larger market share, reaching 21% of total sales in 2010. This has produced two effects: a reduction in average CO2 emissions and a substantial increase in nitrogen oxide emissions. Average emissions from the 2006-2010 sales have remained relatively stable. The commercial diesel vehicles segment shows an important increase in its pollutant emissions in 2007 and 2008, possibly due to an extension in the supply of light duty trucks and SUV EURO III vehicles, since this standard is still accepted in the country, although it is over 10 years old. In the case of particulate matter, there has been no improvement in the national vehicle fleet’s average emissions, except for 2007 when the EURO IV standard took effect in the Metropolitan Region for light duty diesel vehicles.

Government of Chile, Ministry of Energy, 2010

1.3 Status of LDV fleet fuel consumption/CO2 emissions

There are no fuel economy standards for vehicles, but the newly-formed Ministry of Energy has an Energy Efficiency Division mandated with national policy for energy efficiency. There are two main preliminary elements of the emerging energy efficiency policy for light-duty vehicles: 1) an incentive program for the purchase of hybrid electric vehicles and 2) a new vehicle fuel economy labeling system (see section 5.1 below).

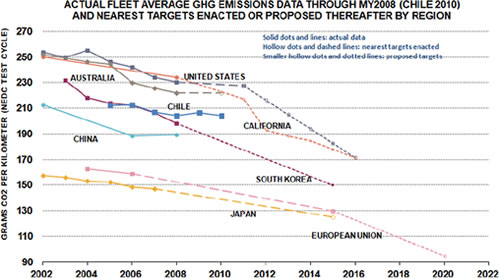

The domestic fleet shows average CO2 emissions similar to the ones observed in South Korea, and close to the ones from Australia and USA. In order to understand this phenomenon, it is necessary to consider that the domestic fleet composition is very particular, because it has important sales in the segment of light duty trucks and SUV’s, typical of the U.S., with plenty of sales in the segment of city cars (class A vehicles), nonexistent in the U.S. It is necessary to consider that the countries mentioned above, unlike Chile, have existing fuel economy standards, so the emissions difference is narrow.

With respect to the EU and Japan vehicle markets, Chile shows a significant lag, with 30% higher emissions.

The reasons are that these countries show a smaller share of pick-up and SUV’s purchases, and have existing or planned strong performance and CO2 emissions regulations. The high average emissions of vehicles sold in the country will mean a significant increase of greenhouse gas emissions, as the vehicle fleet continues to grow in this decade. Figure 4 presents an estimate of the total emissions of the national light and medium vehicles fleet, in an identical scenario to the one observed in 2010, considering the fleet growth according to BBVA4’s projections until 2012 and then based on projected growth rate over the past 5 years. An increase of more than double in 10 years will mean a significant increase of greenhouse gases in the country, because transport is responsible for one third of these emissions.

Related to the growing international concern about the problem of climate change, is the need to reduce dependence on fossil fuels, area in which Chile is extremely sensitive. This was demonstrated during the last crisis in 2008, where the State had to supplement 1 billion US dollars from the Oil Prices Stabilization Fund, along with a significant loss of revenue resulting from the temporary reduction in the gasoline tax. It can be observed in an international comparison that the average performance of the national automotive market is low, corresponding to the year 2010 to 31.2 mpg, which has important implications for future oil demand.

The Mario Molina Center Chile has led an auto market environmental trend study for 2005 - 2008, focused in local pollutants (NOx and PM) and CO2 / fuel consumption. While the CO2 information for vehicles was not available for all models, 3CV allowed access to emission data sets where CO2 emission is available for 65% of the car models. The full results of the study, including estimated baseline auto fuel efficiency of the fleet from 2005, may be downloaded here (Spanish version) and (English version) here.

Source: the ICCT and Centro Mario Molina Chile

2.0 Regulatory Policies

2.1 National Standard

There is no national standard for automotive fuel economy in Chile.

2.2 Import restrictions

Second Hand

In Chile, the importation of used vehicles is banned.

2.3 Technology mandates/targets

There are no technology mandates or targets in Chile at the moment.

3.0 Fiscal Measures and Economic Instruments

3.1 Fuel Taxes

The following taxes are paid on fuel in Chile:

- (i) Taxes on imported products;

- (ii) Specific taxes for fuels used in transport vehicles; and

- (iii) A value-added tax paid on all fuels. Import taxes or tariffs are paid on all imported products, and current rates are around 6% under the general regime.

This rate varies depending on the country of origin and whether it has signed a trade agreement with Chile. The specific tax for fuels used in transport vehicles is applied to gasoline, diesel oil, LPG and CNG.

3.2 Fee-bate

With the help of the Global Fuel Economy Initiative and the International Council on Clean Transportation, Centro Mario Molina Chile designed and proposed a feebate system for Chile in July 2011. Its adoption is still under review, as of June 2013. The system designed for Chile has the advantage of being fiscally neutral and it produces a change towards cleaner vehicles in all segments of the vehicle fleet, as has been the case, for example, in France with the bonus/malus system, and in Denmark. The feebate is more efficient than the incentives for specific technologies, which have only demonstrated being effective in supporting the development of a new technology, such as hybrid vehicles, but that have had a marginal impact on the vehicle fleet.

The proposed benchmark for Chile is 175 grams of CO2 per kilometer, and it is estimated that the incentive and disincentive system will imply a 5% reduction of CO2 emissions from the total national vehicle fleet in 2014, obtaining a total CO2reduction of 2.15 million tons during the next 5 years. Based largely on the French system (see above) but with a constant CO2 price rather than a step function, the proposed system is available here [English,Spanish] in English and Spanish. Based on the feebate proposal, a Chilean Auto Fuel Economy Label was developed for the national market and adopted in April 2013.

3.3 Buy-back

N/A

3.4 Other tax instruments

N/A

3.5 Registration fees

Vehicle registration fees vary inversely based on vehicle age, with the perverse effect of rewarding older vehicle ownership. The primary challenge to changing this structure is equity-based, as poorer people tend to own older cars. The vehicle sales tax system does not reflect vehicle efficiency.

3.6 R&D

The National Commission for Scientific and Technological Research has developed bilateral technology co-operation agreements with the United States, Canada, the European Union, France, Germany and Finland, among others, to develop specific research projects, in particular on non-conventional renewable energy sources.

4.0 Traffic Control Measures

4.1 Priority lanes

Priority lanes exist for public transport and taxis.

4.2 Parking

N/A

4.3 Road pricing

Road pricing, plans to modify land development patterns, etc. – have been included over the years in relevant transportation plans, but implementation has remained elusive.

5.0 Information

5.1 Labeling

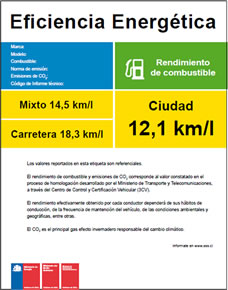

Chile is the first Latin American nation to put in place a national label, mandatory from February 2013. Every car in a show room must have a label in the wind shield showing the fuel economy in kilometers per liter tested in the New European Driven Cycle, including also CO2 emissions and local pollutant emission standards that the vehicle model meets. The information came from the type approval process that is done in Chile in the Center for Vehicle Control and Certification (3CV) of the Transport Ministry of Chile. This is a joint initiative developed between Transport, Energy and Environmental Ministries. The labeling program was designed with Global Fuel Economy Initiative support by the Centro Mario Molina Chile.

Read more about Chile’s fuel economy approach here.

Chile Fuel Economy Label Example

5.2 Public info

A web site with fuel economy and CO2 data for vehicles is planned for launch in 2013 by public authorities, completed with GFEI support: www.compraunautolimpio.cl

5.3 Industry reporting

The Mario Molina Center Chile led an auto market environmental trend study for 2005 - 2008, focused in local pollutants (NOx and PM) and CO2 / fuel consumption. While the CO2 information for vehicles was not available for all models, 3CV allowed access to emission data sets where CO2 emission is available for 65% of the car models. The full results of the study, including estimated baseline auto fuel efficiency of the fleet from 2005, may be downloaded here (Spanish version) and (English version) here.

The text above is a summary and synthesis of the following sources:

- An, Feng and Amanda Sauer. “Comparison of Passenger Vehicle Fuel Economy and Greenhouse Gas Emission Standards Around the World.” Pew Center of Global Climate Change (2004): 1-36.

- An, Feng, et al. “Passenger Vehicle Greenhouse Gas and Fuel Economy Standards: A Global Update.” The International Council on Clean Transport, 2007: 1-36.

- Centro Mario Molina Chile, http://www.cmmolina.cl/

- “Chilean Government adopts fuel economy labeling.” http://www.globalfueleconomy.org/updates/2010/Pages/ChileanGovernmentadoptsfueleconomylabeling.aspx

- “International Comparison of Light-duty Vehicle Fuel Economy and Related Characteristics.” International Energy Agency Working Paper Series, 2010: 1-70.

- Kieffer, Ghislaine, et al. “Chile Energy Policy Review: 2009.” International Energy Agency (2009): 1-270.